Why Investment Banks Should Not Buy Hedge Funds |

Date: Wednesday, May 7, 2008

Author: Seeking Alpha.com

Last week Citigroup (C) told us, on Page 17 of their 10-Q, about the fate of their $800mn purchase of Old Lane Partners. Vikram Pandit, now the CEO of Citigroup, was the founder of Old Lane. Citigroup may have gotten Pandit and his top lieutenant, John Havens, but it would be an understatement to say that the fund they purchased has failed to live up to expectations.

In the 10-Q Citigroup told us that all of the fund's outside investors had redeemed their money in the fund. The peak AUM of the fund was 4.5bn after it launched with $2bn in capital. Citigroup bought Old Lane when it had an AUM somewhere between these two numbers. Before Citigroup bought the fund Old Lane had an unremarkable track record and since the purchase it has done poorly. No wonder investors have chosen to redeem their investments.

Citigroup had to writedown the value of the $800mn it invested by $202mn this year. Other analysts have decried the failure of Old Lane within Citigroup as an even bigger loss since Citigroup shutdown its home-grown Tribeca Capital Management fund when it bought Old Lane. This view is probably mistaken because Tribeca also had sleepy returns, a function being a diversified multi-strategy fund facing a diminishing ability to generate great risk adjusted returns because of its large size, and was probably on the edge of being redeemed by the remaining outside investors in the fund. The failure of Old Lane and Citigroupís announcement that it is going to restructure the fund should not surprise us. Allow The Prince to explain.

The story of Old Lane reminds The Prince of one maxim that should now be abundantly true. Investment banks should not be in the business of buying hedge funds. If they must own hedge funds to accomplish other goals, like talent retention, they should create such funds organically. Investment banks should grow hedge funds organically if they must grow them at all and not go out and buy them. The risks inherent in a purchase such as failure to properly align incentives using compensation and key person or human capital risks combined with high valuations makes any purchase of a hedge fund by an investment bank a value destroying endeavor.

First, we have the failure to align incentives in a large hedge fund once an investment bank makes a purchase. Structuring compensation to reward and retain employees at a hedge fund is the most important decision a portfolio manager/CEO makes at a hedge fund. It must pay its people enough to retain them and also give their employees compensation in forms that will encourage them to stay and not leave for other funds or to start their own funds.

Once this compensation structuring is taken out of the hands of the portfolio manager, who is the main owner, and the new owner, i.e. the investment bank, has a say, this tough decision becomes nearly impossible to get right. The best talent will realize that since a large asset gatherer like Old Lane owned by Citigroup is highly risk averse, there will be less opportunity for the talent to take risks.

If the talent feels like they are not able to take risks that present attractive opportunities for the fund (and their own personal compensation as a result) because losses that could materially change the performance of the fund could result, they will realize that their risk taking expertise can be better rewarded at other firms. There is absolutely no way that investment banks can properly maintain incentives in the hedge funds they buy to retain talent and adequately reward talent.

Second, what are the assets that hedge funds like Old Lane use to generate earnings? Ultimately, a hedge fundís assets are the people it employees and the expertise they bring to bear on the investing done by the fund. When an investment bank buys a fund they are exposing themselves to human capital and key person risks that must be taken into account. What if the main portfolio manager tries to leave the fund or worse just stops working very hard because he or she has already cashed out in the sale? What if the portfolio managerís top subordinates and their groups leave? It is just impossible for an investment bank to protect their investment when their assets can be walking out the door or dramatically lowering their productivity because incentive structures based on compensation are misaligned. These first two points about why investment banks should not buy hedge funds are inextricably linked and the two points affect each other.

Yet, these two points alone do not make a complete case for why investment banks should not buy hedge funds. These first two points only point to serious risks that should dramatically impact the valuation that a bank is willing to pay to acquire a hedge fund. So, if banks take into account these two major risks to the value of the hedge funds they are buying we should see low valuations, right? Wrong. The valuations paid for hedge funds paid by investment banks have been off the charts and they are downright ridiculous when taken in-light of the two points above made about risks to the value of a hedge fund bought by an investment bank.

Which brings us to The Princeís final point. The valuations given to hedge funds by investment banks are simply too high. They are too high in light of the two aforementioned risk points. They are also too high because the banks are not making reasonable assumptions about the future of these funds. What do I mean by "reasonable assumptions about the future of these funds"? There are a number of assumptions that they are making which are crazy. First, they are not adequately factoring in the risk of redemptions if the fund has a bad year or under performs. This risk, which is not that unlikely, basically makes the asset the bank bought worth nothing. They are also not taking into account the fact, that as a general rule of thumb, the larger a fund, the lower its returns will be. Larger funds simply do not have as many profitable ideas to put money into. They have trouble deploying all their capital into their best ideas and often invest capital in ideas that will not generate Alpha.

Returns to investors do decline when funds grow in size, any savvy investor in hedge funds will tell you this. In fact, some institutional investors in hedge funds will not invest in large funds because they do not think they provide enough value for their fees. The larger a fund gets, the more it becomes an asset gatherer trying to make gains on management fees and earn market returns so that its capital does not get redeemed. The larger a fund gets, the more risk averse its behavior becomes, because it has a lot more to lose on the management fee side if it gets aggressive, shows a loss, and then gets a large chunk of its AUM redeemed.

In light of these facts, investment banks, in their valuations of hedge fund partnerships, are probably assuming that returns to investors will be better than they are likely to be in reality. Considering all the points listed, banks should be a lot more conservative when they predict the returns that a hedge fund will earn for its investors. Being more conservative in this estimate will lead to lower projections of revenues from management fees, which will impact valuation.

The Prince also believes that investment banks are probably not properly estimating compensation expense. Many investment banks may believe that they can cut compensation expense and still retain talent once they buy these hedge fund partnerships. That belief is pure fantasy. Investment banks should pay low valuations for hedge fund partnerships for no other reason than the cash flows from such partnerships are going to be unpredictable. This just comes with the territory of a business where most of your variability in earnings comes from an incentive fee pegged to performance and your capital can be redeemed subject to the lock-up and quarterly redemption schedule.

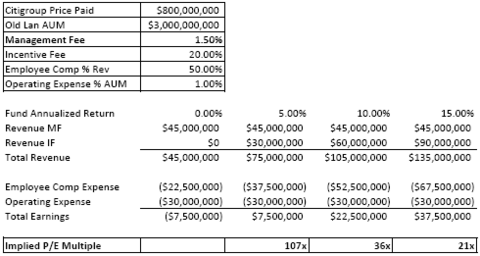

To demonstrate the points made above, The Prince did a quick and dirty analysis of the acquisition of Old Lane by Citigroup. The assumptions and ranges are based on The Princeís experience in Prime Brokerage. Obviously there are many things that are not absolutely correct here, like the fact that the management fee is paid each quarter not in a lump sum by the investors. I am also assuming that Old Lane has an incentive fee of 20% and a management fee of 1.5%, which may actually be high given the size of the fund.

The Prince is also assuming that at the time of Citigroupís purchase Old Lane had $3bn in assets under management. The fund launched with $2bn and it is difficult to tell what its size was when Citigroup acquired it, but pegging it at $3bn is generous. The analysis below is meant to push the envelope in an effort to justify the valuation given to Old Lane by Citigroup.

Click to enlarge

As you can see, the price looks absolutely ridiculous for the kind of business that is prone to the kinds of risks and unpredictable cash flows outlined above. The analysis also assumes no hurdle rate, which would make the analysis have Citigroup looking even worse. Furthermore, it assumes that operating expenses like office leases, infrastructure etc. will run at only 1% of AUM which is probably low considering that Old Lane has a few hundred employees and offices on multiple continents.

The 20% incentive fee may even be high, since it is almost a given that to raise the initial $2bn in AUM Pandit and company had to grant fee breaks to investors willing to write big checks on day one. The 50% of revenues going to employee compensation may also be too low. While this is a good assumption to make at investment banks when it comes to estimating employee compensation expense, it probably does not approximate hedge fund employee compensation expense, which is probably a higher percentage.

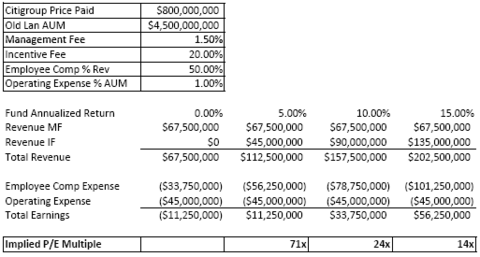

Some may say well Citigroup must have been expecting the fund to return more than 10% on average, or grow in size to justify the multiple paid. This expectation, if Citigroup held it, is foolish for many of the reasons listed above. These reasons include the fact that investment returns usually decline as fund size increases and the unpredictability of investment returns which leads to unpredictable earnings for the hedge fund. Letís cut them a break and look at the valuation if Citigroup expected Old Lane to run at an AUM of $4.5bn and earn 10% each year.

Click to enlarge

24x earnings is still a crazy sum to pay considering the unlikelihood that these assumptions will play out. Old Lane did reach a peak AUM of 4.5bn before getting all its outside money redeemed and it never earned anything near a 10% per year return. Now Citigroup is faced with the fact that it paid $800mn for something that is worth close to nothing, and will be worth nothing once all the talent leaves Old Laneís sinking ship.

Yet, Citigroup is not the only bank that is giving crazy valuations to hedge funds when they buy them. Morgan Stanley (MS) and others have also played in this water. Some, like UBS (UBS), have even got burned (take a look at UBSís write downs related to internal hedge fund Dillion Reedís credit exposure). It is time for investment banks to stop buying hedge fund partnerships. Because of all the arguments in this post, buying these things is unlikely to create value for a bank. The risks are too great and the returns are to small or too unpredictable to compensate.

Pandit and his top lieutenant, John Havens, were admired and respected in Morgan Stanleyís institutional securities division. Yet, selling this firm to Citigroup at $800mn then assuming posts at Citigroup looks like the height of blind self-enrichment. In a phrase, "whereíd you go wrong sons." The only problem with this view is that someone at Citigroup was dumb enough in the first place to pay $800mn for Old Lane, thus giving us yet another example for why investment banks have no business purchasing hedge funds.

Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.